QUALITY CYCLING CLOTHING SINCE 1996 - THE UK'S FIRST RETRO MANUFACTURER

QUALITY CYCLING CLOTHING SINCE 1996 - THE UK'S FIRST RETRO MANUFACTURER

RETRO APPAREL

COLLECTIONS

Cycling Clothing

ACCESSORIES

The Milk Race - The squid and the whale

February 26, 2019 6 min read

Join respected author & journalist Herbie Sykes who looks back on the Milk Race from an Eastern European and Soviet Union riders point of view in this insightful piece.

That the Milk Race was the greatest event on the British calendar goes without saying.

However, between 1967 and 1984, the years during which it was a truly international affair, only two Brits ever won it. Les West and Bill Nickson were both extravagantly gifted bike riders, but even so, their having defeated the “amateurs” of the communist countries beggars belief.

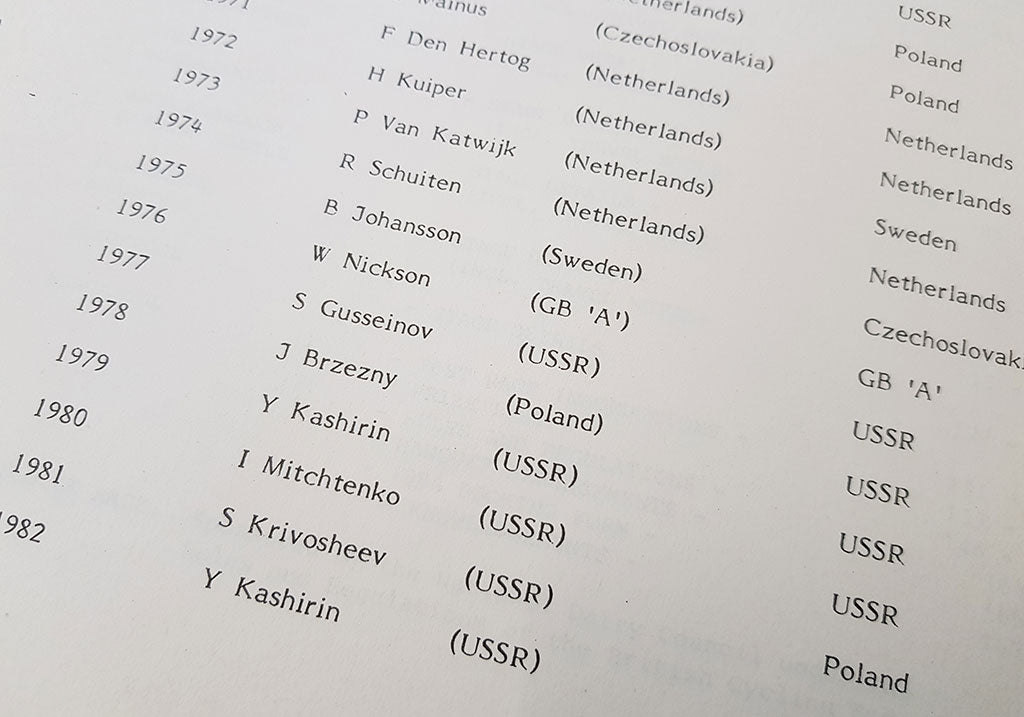

The Roll of Honour, taken from the 1985 Milk Race Manual

Sport was a political blunt instrument during the Cold War, and it mattered a very great deal behind the Iron Curtain. As such the Eastern Bloc riders’ training and preparation was infinitely more “sophisticated” than that of western professionals, let alone British plumbers, traffic wardens and factory workers.

In describing the 1979 Milk Race, Phil Liggett likened the Soviet Union’s domination to “a whale gulping down plankton”. They’d won six of the twelve stages, Juri Kashirin had dominated the GC and the points, and the team competition had been, well… no competition at all. Eastern Bloc riders had occupied the top six placings and Ray Lewis, the best Brit, had been 14th. Miraculously he’d won a stage as well, as had Gerry Taylor and Joe Waugh. Miraculous because the odds were, as near as made no difference, insurmountable for the home-grown riders.

Salaried sport was anathema to communist ideology. That, however, doesn’t alter the fact that the Soviet Bloc riders were professional in all but name, and didn’t stop them competing in the west. The continent boasted an amateur stage racing circuit every bit as diverse as its professional counterpart, and much more intriguing. Not for nothing were the Giro delle Regioni and the Tour de l’Avenir broadcast live in Italy and France, and not for nothing was the Peace Race the biggest annual participation event (sporting or otherwise) in the world. Throw in the Olympia Tour in Holland, the GP Guillaume Tell in Switzerland and any number of others like them and you had, in effect, two cycling seasons running in parallel.

One my fondest memories as an up and coming road cyclist was the Milk Race. Other than being selected for the World Championship team, it was probably one of the most premier selections that could be made as a top national amateur rider in the USA during the time period.

There were really only two top international amateur or pro-am stage races during that time frame and for us westerners we had the Milk Race… and for the Eastern Europeans it was the Peace Race. The Milk race for us American’s was especially fun and challenging as we were able to at least get close to European soil and test our fitness and skill against Europe’s best and not only with amateurs, but a smattering of pro teams.

Fairly tough terrain, tough competition and challenging weather comes to mind when I recall this event. I remember three things clearly about the Milk Race; My cycling shoes never dried out during the whole race, I chugged about 3 or 4 glasses of milk after each stage as they always gave us those at the finish line.. and I won a massive Fruit Cake prize at one stage for being the top American in one particular town where the local Baker Lady was an American. For some reason none of teammates would help me eat the fruit cake, so I had it all to myself!

John Tomac. UCI Mountain Bike World Cup & World Championship XC Winner 1991.

For the Eastern Bloc riders, the season comprised two distinct cycles. The first, January to April, was preparation for the Peace Race. Full-time, state-sponsored riders would be dispatched to Africa for training camps, and when they came home they’d split into two or three groups. They’d compete in events like the Tour of Vaucluse, before a final elimination during the last week in April. The Soviets would send six riders to Brittainy for the Ruban Granitier, another six to Central Italy for the Giro delle Regioni. There they’d be hammer and tongs with the Poles, the Czechs and the East Germans, and the best six from each would win the ultimate prize, a ride at the Peace Race starting 8 May.

Those who didn’t make the final cut would stay in the west to race smaller events and train. Then, if they were lucky enough and brilliant enough they’d catch a ferry to Britain for the Milk Race. Those twelve up-hill-and-down-dale days were the beginning of phase two of the season, culminating in their own national tours, the Amateur World Championship road race and, every four years, the Olympics. The Milk Race was a preparatory event for those and victory in Britain, though expected, was less important geopolitically.

Most remember their fortnight in Britain as the very height of luxury. Ostensibly there was no money in amateur stage racing, and they were accustomed to uncomfortable nights spent in the local school or theatre. By the standards of the time the Milk Race accommodation, often bed and breakfasts on the English coast, was truly opulent, with a £2 per day "pocket money" allowance for every rider and team helper in the race 1980s.

As “diplomats in tracksuits”, socialist athletes were among the tiny minority able to cross the Berlin Wall. In winning they were seen to be demonstrating the moral and philosophical superiority of communism but – and here’s the paradox – it made highly accomplished capitalists of them. By Eastern European standards, they were highly remunerated anyway, but the Milk Race was perceived as a land of milk and honey.

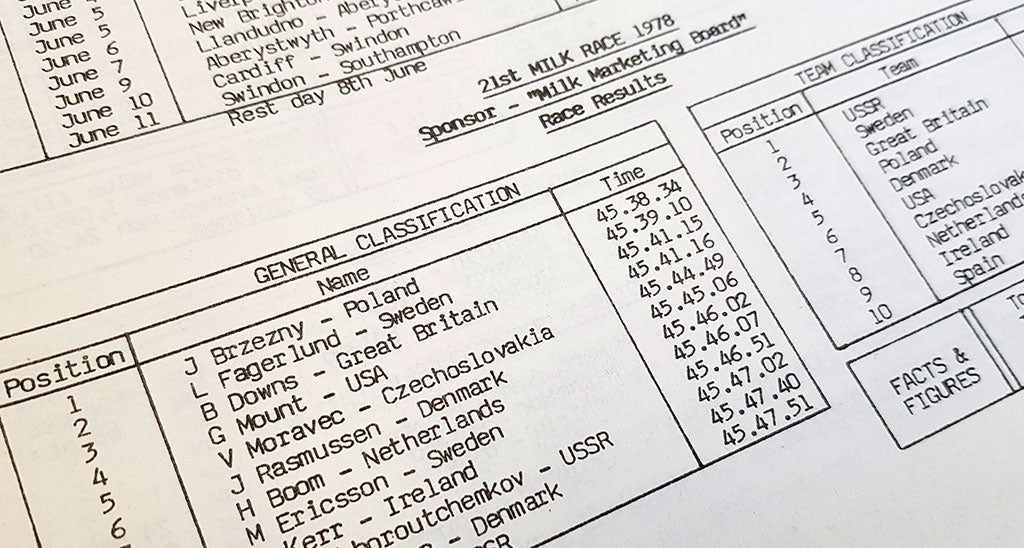

Old school, hand-typed results of the 1978 Milk Race - now a practice firmly in the past.

The prizes at the Milk Race were incredible by amateur standards of the time. I earned $500 when I won it, and the average wage in Poland was about $20. We had an agreement that we’d hand 40 per cent of our winnings back to the federation, and they gave us a certificate stating that we’d received prizes as distinct to cash.

Jan Brzeźny. Milk Race winner 1978.

For the Soviets and East Germans in particular, sport and politics were indivisible. Their riders had to be seen to have the best componentry, but that was manufactured on the other side of the wall in capitalist Italy. It was a classic example of the rank hypocrisy at the heart of amateur sports, and so were the “missing” and “stolen” Colnagos they left behind. The Russian Federation forbade its riders from receiving cash but turned a blind eye to the consequences. It was implicit that the prizes, won in lieu of cash, would be exchanged for hard currency. That currency was the US$, and the Russians, in particular, would trade just about anything to lay hands on it. Their jerseys and innertubes, their primes and prizes, the very bikes they rode on…

Like all Milk Racers, Brzeźny remembers shell-shocked guys climbing off on short, spiteful English climbs. They’d come to Britain with their 42x21 gear ratios, and be totally undone by her 20 per cent gradients. The other abiding memory is the anti-Soviet alliances formed on the road. In Britain, we tended not to distinguish between the “communist” riders, but the reality was much more textured. In that 1978 Milk Race a mechanical almost cost Brzeźny his yellow jersey, but the brilliant Czech rider Antonìn Bartoníček came to his aid. The Poles kept the race lead, and the Czechs were rewarded with a stage win at Penrith.

Of course I remember the Devil’s Staircase because it was such an iconic climb, but also these tight, windy little country lanes. I also remember a stage at the 1982 race, to Aberystwyth. It was early in the race and the Russians decided they wanted to smash it up. Kashirin and two others attacked, and I got on with a Swiss guy.

We stayed away all day and I remember thinking how incredible it was that they could be so strong. I didn’t take anything and knew nothing about “preparation”. With the benefit of hindsight, it seems probable that they knew much, much more about it. The Milk Race was essentially an unequal struggle between the six Soviets and the rest of us.

We’d win the odd battle here and there, but I suppose they always won the war.

Morten Sæther (Norway). 1981 Stage winner.

It goes without saying that we tend to undervalue the Milk Race. Its cardinal points were Skegness, Llandudno and Blackpool, quintessentially British working class mining resorts. As Brits, we always did have an inferiority complex where cycling was concerned, and the Milk Race was resolutely and at times painfully British. That said it offered a glimpse, however fleeting, of people and cultures we wouldn’t otherwise have known. We didn’t necessarily understand it at the time, but it formed an intrinsic part of a giant travelling propaganda exercise, its constituents pawns in the sporting and geopolitical jigsaw puzzle.

And, lest we forget, it was a cracking good bike race.

RIP The Milk Race.

If you enjoyed this article, we've plenty of other Milk Race blogs now published online.

Also in News and articles from Prendas Ciclismo

Prendas' Best-Selling Caps of 2024

January 21, 2025 4 min read

With 2024 in the books, we're looking back at your favourite caps of the year. From cult classic movies to the jungle with a whole lot of Italian flair, check out our best-sellers and grab a new cap!

Vas-y Barry! Hoban wins Ghent-Wevelgem for Gan Mercier Hutchinson

May 15, 2024 8 min read

In an extract from his autobiography, Vas-y Barry, the only British winner of Ghent-Wevelgem, Barry Hoban tells how he won the cobbled classic in 1974, beating Eddy Merckx and the cream of Belgian cycling.

Our Best Selling Caps of 2023

January 15, 2024 4 min read

We know caps here at Prendas Ciclismo, and we know that you love all the styles we have on offer. So every year, we look back at our best-selling cycling caps for the previous year for you to discover a few new styles. Is your favourite cycling cap featured on our list? Read on and see!

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …